The Esopus Wars

There were two “Esopus Wars” between the Lenape Indians also called the Esopus Tribe and the New Netherland colonists between 1659 and 1663. The first battle was instigated by settlers and the second war was due to a grudge on the part of the Indians.1.

Table of Contents

Before Colonization

Before European colonization, the Kingston area was inhabited by the Esopus people, a Lenape tribe that was estimated to be about 10,000 people living in small communities b 1600.

In 1609, Henry Hudson explored the river which was named after him, leading to the first contact between the Esopus people and Europeans. Dutch settlers built a trading post in what is now Kingsston, New York, in 1614. The Esopus tribe used the land for farming, and they destroyed the post and drove the settlers back to the south.

Colonists established a new settlement in 1652 in the same area, but the Esopus Indians again drove them out. The settlers returned once again in 1658, as they believed the land to be good for farming. They built a stockade (see my post Esopus / Wiltwyck / Kingston, New York for details about the Stockade) to defend the village and named the colony Wiltwyck (also spelled Wiltwijck, Wildwiyck, etc.). Skirmises continued, but the esopus were not able to repel the settlers and they eventually granted the land to them.

The First of the Esopus Wars - 1659-1660

The First Esopus War was a conflict, largely started by fear and misunderstanding on the part of the settlers. It began on September 20, 1659 and ended July 15, 1660.

On September 20, 1659, after the Esopus Indians had finished farm work for the colonists and had received their pay in brandy, a drunken native fired a musket in celebration. Although no one was hurt, some of the townsfolk suspected foul play. Although a group of soldiers investigated and found no bad intentions, a mob of farmers and soldiers attacked the offending natives. The Esopus natives returned with reinforcements, raided the colonist settlements outside the stockade, destroying crops, killing livestock and burning buildings. The war party later besieged the walled settlement of Wiltwyck.

The colonists were outnumbered, but were able to hold out and make some small attacks, including burning the Indians’ field to starve them out. The settlers received reinforcements from New Amsterdam. The war concluded July 15, 1661, when the Indians agreed to trade all the land of Esopus, for crops lost with half the year”s harvest for 1660 and 1661.

Tensions remained between the Esopus and the settlers, however, eventually leading to the second war.

The Second of the Esopus Wars - 1663

On June 7, 1663, while many of the men and older children were away from the villages working in the fields, the Esopus Indians raided and burned the villages of Niew Dorp (Hurley) and Wiltwyck (Kingston), carrying away captive the wife and two children of Jan Joosten, the wife and three children of Louis Du Bois, and two children Mattheus Blanchan and the wife and one child of Antoine Crispell. They were not rescued until 3 months later. Names of the children were not listed, but the following are the most likely taken:

- Macyke Hendricse, wife of Jan Joosten and two children [most likely Geertje Crom, 7 and Joost Janse, 3].

- Catherine Blanchan, wife of Louis DuBois and three of their children. [Most likely Abraham, 6; Isaac, 3; and Jacob, 1 1⁄2. Stories passed down say baby Sara Du Bois was one of the children, but Sara was not baptized until 14 Sep 1664, and typically children were baptized shortly after their birth, so I doubt that Sara was one of the children. Joost Jans will later marry Sara].

- Maria Blanchan, wife of Antoine Crispell and one child. [Most likely their daughter, Maria, 1 1/2].

- Two young children of Mattheus and Magdelina Blanchan. [Most likelyy Mattheus Jr, 8 and Elizabeth, 12].

Capt. Martin Kregier’s Journal “The Second Esopus War”2 documents the events shortly after they occurred. You can read the complete Journal in the Book The Documentary HIstory of the State of New York by Hon. Christopher Morgan, Secretary of State by E. B O’Callaghan, M.D. Vol. IV. This link will take you to a free digitized copy at archive.org beginning on page 37. I have recapped the story below.

The Indians had just been invited by the Director-General to meet him, and renew the peace, and they responded “If peace were to be renewed with them, the Honorable Heer Director General should, with some unarmed persons, sit with them in the open field, without the gate, as it was their own custom to meet unarmed when renewing peace or in other negotiations.” By then, unmindful of the preceding statement, surprised and attacked us between the hours of 11 and 12 o’clock in the forenoon on Thursday the 7th instant.

Entering the bands through all the gates, they divided and scattered themselves among all the houses and dwellings in a friendly manner, having with them a little maize and some few beans to sell to our Inhabitants, by which means they kept them within their houses, and thus went from place to place as spies to discover our strength in men. The people were scattered about, at their various occupations in town and field. In this condition of affairs, on June 7th, 1663, the Indians entered within the stockade and under various pretexts scattered themselves through the town.

After they had been about a short quarter of an hour within this place, some people on horseback rushed through the Mill gate [now corner of North Front and Greene] from the New Village [Niew Dorp, now Hurley] crying out “The Indians have destroyed the New Village!” With these words, the Indians here in this village immediately fired a shot and made a general attack on our village from the rear, murdering our people in their houses with their axes and tomahawks, and firing on them with guns and pistols; they seized whatever women and children they could catch and carried them prisoners outside the gates, plundered the houses and set the village on fire to the windward, it blowing at the time from the South.

The remaining Indians commanded all the streets, firing from the corner houses which they occupied and through the curtains outside along the highways, so that some of our inhabitants, on their way to their houses to get their arms, were wounded and slain. When the flames were at their height the wind changed to the west, were it not for which the fire would have been much more destructive.

So rapidly and silently did Murder do his work that those in different parts of the village were not aware of it until those who had been wounded happened to meet each other, in which way the most of the others also had warning

The greater portion of our men were abroad at their field labors, and but few in the village. Near the mill gate were Albert Gysbertsen with two servants, and Tjerck Chlaesen de Wit; at the Sheriff ‘s, himself with two carpenters, two clerks and one thresher; at Cornelius Barentsen Sleght’s, himself and his son; at the Domine’s, himself [Domine Blom] and two carpenters and one labouring man; at the guard house, a few soldiers; at the gate towards the river, Henderick Jochemsen and Jacob the Brewer; but Hendrick Jochemsen was very severely wounded in his house by two shots at an early hour. By these aforesaid men, most of whom had neither guns nor side arms, were the Indians, through God’s mercy, chased and put to flight on the alarm being given by the Sheriff.

Capt. Thomas Chambers, who was wounded on coming in from without, issued immediate orders to secure the gates; to clear the gun and to drive out the Savages, who were still about half an hour in the village aiming at their persons, which was accordingly done. After these few men had been collected against the Barbarians, by degrees the others arrived who it has been stated, were abroad at their field labors, and we found ourselves when mustered in the evening, including those from the new village who took refuge amongst us. The burnt palisades were immediately replaced by new ones, and the people distributed, during the night, along the bastions and curtains to keep watch.

But though the ruthless enemy had been driven out, and the gates shut against them, the scenes within were most distressing. Says an account, written at the time “There lay the burnt and slaughtered bodies, together with those wounded by bullets and axes. The last agonies and lamentations of many were dreadful to hear.”

The captives were taken forward through the forests. They knew not who lay dead in the half- burnt town, or what terrible fate awaited them. In that captive company were one man, twelve married women, and thirty-one children. All of the women were mothers with their children, except one who had been but lately married, and was driven from her young husband, each ignorant of each other’s fate. Ten children were there without father or mother.

They were separated from each other, and were constantly removed from place to place to avoid rescue. Some were in charge of old squaws. Others were held in particular families, and others still were required to accompany the Indians in their wanderings, though the first thought was to repair the fort and stockades. There were nine men, three soldiers, four women (wives), two with child, and two children killed at Wildwyck. Three men were killed in the New Village [Niew Dorp]. This does not include the soldiers wounded or killed during the search that would last until January.

On June 16th, Lieut. Christian Nyssen arrived with forty-two soldiers and on July 4th Captain Martin Krieger arrived with a larger force in two yachts, and ample military supplies. But it would be a long summer of searching for the captives.

Although most would be rescued by September 5th, there were seven who would not be rescued for several more months. Although the recovery dates of the captives was documented, the names associated with the captives was not written except for one of the final captives, was named as Albert Heymans’ oldest daughter. The summer passed in negotiating with the Indians for their return, and in guarding the gathering of the harvest.

We can only assume that the fathers and husbands were part of the search parties, but they also had to continue to provide for the families and making sure the crops were tended to. They still needed to be fed and daily life had to continue in the Stockade.

Over the following months, there were a number of search parties sent out to search for the captives. The Indians had disbursed the captives among them and spread out, not keeping them all in one place together. During the summer there were at least 14 captives rescued as follows:

- 12th July. Three children.

- 13th July. Mr. Gysbert’s wife had been taken prisoner, but had effected her escape.

- 16th July. One girl.

- 19th July. Two women and two children.

- 20th July. Three of the prisoners (no mention as to whether they were children or women)

- 24th July. A female

- 20th August. A woman and a boy.

–

A captured Wappinger Indian was employed to guide the rescuing party, having promise of his freedom and a cloth coat if he led them aright, but death in case of treachery. The place where the captives were held was the “New Fort,” six miles from the junction of the Shawangunk kill or with the Wall kill. The “Old Fort” was on the Kerhonksen, in Warwarsing. The Indian instructed the party of whites to ascend the first big water (Rondout) to where it received the second (Wall kill); then ascend the second big water to the third (Shawangunk), and near its mouth they would find the Indian stronghold. Thee party set out from Fort Wiltwijck September 3rd.

The rescuing party pressed on its rough way with their Wappinger Indian guide, and Christofful Davids as interpreter, and on the 5th of September they reached the vicinity of the New Fort. The following is Captain Kregier’s account, where 23 more captives were rescued:

“September 5th. Arrived, about two o’clock in the afternoon, within sight of their fort, which we discovered situated upon a lofty plain. Divided our force in two Lieutenant Couwenhoven and I led the right wing and Lieutenant Stillwell and Ensign Niessen the left wing. Proceeded in this disposition, along the hill so as not to be seen and in order to come right under the fort; but as it was somewhat level on the left side of the fort, and the soldiers were seen by a squaw who was piling wood there, and who sent forth a terrible scream which was heard by the Indians, who were standing and working near the fort, we instantly fell upon them.

The Indians rushed forthwith through the fort towards their houses, which stood about a stone’s throw from the fort, in order to secure their arms and thus hastily picked up few guns and bows and arrows; but we were so hot at their heels that they were forced to leave many of them behind. We kept up a sharp fire upon them, and pursued them so closely that they leaped into the creek, which ran in front of the lower part of their maize land. On reaching the opposite side of the kill [river], they courageously returned our fire, which we sent back, so that we were obliged to send a party across to dislodge them.

In this attack, the Indians lost their chief, named Japequanchen, fourteen other warriors, four women and three children, whom we saw lying both on this and on the other side of the creek. But probably many more were wounded when rushing from the fort to the houses, when we did give them a brave charge. On our side, three killed and six wounded; and we have recovered three-and- twenty Christians, prisoners, out of their hands. We have also taken thirteen of them prisoners, Both men and women.”

The fort was a perfect square, with one row of palisades set all round, being about fifteen feet above and three feet underground. They had already completed two angles of stout palisades, all of them almost as thick as a man’s body, having two rows of portholes, one above the other; and they were busy at the third angle. These angles were constructed so solid and so strong as not to be excelled by Christians. The fan was not so large as the one we had already burned.

The Christian prisoners informed us that they were removed every night into the woods, each night into a different place, through fear of the Dutch, and brought back in the morning. But on the day before we attacked them, a Mohawk visited them, who slept with them during the night. When they would convey the Christian captives again into the woods, the Mohawk said to the Esopus Indians. –‘What! Do you carry the Christian prisoners every night into the woods? To which they answered ‘Yes.’ Whereupon the Mohawk said, ‘Let them remain at liberty here, for you live so far in the woods that the Dutch will not come hither, for they cannot come so far without being discovered before they reach you.’ Wherefore they kept the prisoners by them that night.

The Mohawk departed in the morning for the Menacing and left a new blanket and two pieces of cloth, which fell to us also as booty; and we came just that day, and fell on them so that a portion of them is entirely annihilated”

Although twenty three of the captives were rescued in September, there were still seven captives left to be rescued. Kriegers journal shows the following entries, showing negotiations for the last seven captives.

28th of November. about one o’clock in the afternoon a Wappinger Indian came to Wildwyck with a flag of truce; reports that a Wapinger Sachem lay at the river side near the Redoubt with venison and wished to have a wagon to convey the venison up for sale, which was refused. The said Indian told me that the Sachem had not much to say; added further, that the Hackingsack Indians had represented that four of the Esopus Indians, prisoners in our hands, had died. Whereupon the Indian prisoners were brought out to the gate to him, to prove to him that they were still living and well. Sent him down immediately to his Sachem at the river side, to say to him that we should come to him tomorrow.

29th ditto. At day break had notice given that those who were desirous of purchasing venison from the Indians should go along with the escort to the river side. Accompanied the detachment to the shore and conversed with the Sachem in the presence of Capt. Thomas Chambers and Sergeant Jan Peersen. he said, he had been to receive the Christian prisoners and should have had them with us before, had he not unfortunately brunt himself in his sleep when lying before the fire; shewed us his buttock with the mark of the burn which was very large; Also said, that six Christian Captives were together at the river side, and gave ten fathom of sewan to another Indian to look up the seventh Christian who is Albert Heyman’s oldest daughter, promising us positively that he should restore all the Christian prisoners to us in the course of three days, provide it did not blow too hard from the North; otherwise, he could not come before the fourth day. We, then, parted after he had, meanwhile, sold his venison. he left immoderately in his canoe.

2nd December. ……Which Sachem brought with him two captive Christian children, stating to us that he could not, pursuant to his previous promise of the 29th November, bring along with him the remainder, being still five Christian captives, because three were at their hunting grounds, and he could not find them, that another Indian was out looking for them; the two others are in his vicinity, the Squaw who keeps them prisoner will not let them go, because she is very sick and has no children, and expects soon to die; and when he can get Albert Heymans’ oldest daughter, who is also at the hunting ground, and who he hath already purchased and paid for; then he shall bring the remainder of the Christian captives along.

No other mention of the remaining 5 captives was made in the Journal, but we can only assume that they were returned and the remaining Indian captives released by the end of the year. It has been assumed the DuBois, Van Meteren, Blanchard and Crispell family members were rescued in September.

The Esopus Indians fled, and the colonists led by Captain Marin Cregier pillaged their fort before retreating, taking supplies and prisoners. This effectively ended the war, although the peace was uneasy.

DuBois Family Tradition

The following is quoted from The Life and Times of Louis DuBois on the DuBois Family Association website.3

“In this historical recital, we have followed authentic documents. But there is a history among us for which we are not dependent on State archives. The traditions of these early times have been preserved with remarkable clearness among the descendants of Louis DuBois. Most of them I have myself heard many times from my grandfather and great-uncle. We associated them with the historical narrative already given, and we think correctly. The approach of the rescuing party at the New Fort was betrayed by their dogs, which ran on in advance and centered the Indian came:

The cry was at once raised and repeated, “Swanekers and deers,” “White man’s dogs,” and thus and stealthy approach was betrayed. (This jargon, swanekers and deers, with its translation–white man’s dogs–has been preserved among us for two centuries, wholly by tradition. You may imagine, therefore, how much I was interested in discovering lately, by contemporaneous documents, that the word “swanekers” was the Indian word for “white man” among the Long Island Indians. In this instance, our tradition is verified.)

It is also said, that as the whites neared the fort Louis DuBois pressed on ardently, and perhaps incautiously, in advance. Thus exposed, an Indian, from behind a tree, was about to draw his bow for the fatal shot. But, for some cause, the arrow did not rest upon the bowstring, and DuBois instantly sprang upon him the agility and strength of a lion, and dispatched him with his sword. One tradition has it that DuBois ran him through with such force that the sword entered a log, and had to be withdrawn by placing his foot upon the prostrate body, and thus jerking it away by main strength.

“After this,” says the account given in the DuBois Family Record,’ a consultation was held as to what course it was best to pursue. They agreed to wait till the dusk of the evening, that they might not be discovered at a distance, and then to rush upon them with a loud shout, as though a large force were coming to attack them, rightly judging that the Indians would flee, and leave their prisoners behind. The savages were engaged in preparations for the slaughter of one of their prisoners and that none other than the wife of DuBois.

She had been placed on a pile of wood, on which she was to be burned to death. For her consolation, she had engaged in singing psalms, which having excited the attention of the Indians, they urged her by signs to resume her singing. She did so, and fortunately continued till the arrival of her friends. In good time her deliverers came. The alarm of their approach was given by the cry of ‘White man’s dogs–white man’s dogs;’ for while they were listening to the singing of their wives, the dogs had gone on and entered the encampment.

They raised a shout. The Indians fled, and, strange as it may seem, the prisoners also fled with them, but DuBois, being in advance and discovering his wife running after the Indians, he called her by name, which soon brought her to her friends. Having recovered the prisoners, they returned in safety by the way which they went. “The recovered captives informed their husbands that they were soon to be sacrificed to savage fury, and that they had prolonged their lives by singing for their captors, and were just then singing the beautiful psalm of the ‘Babylonish Captives.’ when they heard the welcome sound of their delivers’ voices.”

The Tradition concerning the impending fate of Catherin DuBois at the time of rescue is not credited by Mr. E. M. Ruttenber, the Orange County historian, who states his objections as follows:4

“The story was repudiated as a statement of fact. First, on the authority of Indian customs. We do not recall a single instance where a woman was burned at the stake by the Indians. They killed female prisoners on the march sometimes, when they were too feeble to keep up, but very rarely indeed after reaching camp. – Mrs. DuBois and her companions had been prisoners from June 7th to September 5th, or nearly three months before they were rescued from captivity. During all that time, they had been guarded carefully at the castle of the Indians, and held for ransom or exchange, to which end negotiations had been opened, the Indians asking especially the return of some of their chiefs who had been sent to Curacoa and sold as slaves by Governor Stuyvesant. Second: documentary evidence concerning the events of that period is entirely against the tradition. The written record is, that when the Dutch forces surprised the Indians, the latter were busy in constructing a third angle to their fort for the purpose of strengthening it, instead of being engaged in preparations for burning prisoners. The Prisoners were found alive and well, and no complaint is recorded of any ill treatment, not even that their heads had been shaved and painted, as had been customary. Every night, says the record, they were removed from the castle to the woods, lest the Dutch should recover them before negotiations for their release were consummated. The entire drift of the record narrative is against even the probability of an intention to burn, much more so of preparation to do so.”

I will leave it to the reader to form their own opinion on the final events. Regardless of the details, we know that most of the captives were held for almost 3 months. Most of the stories written, assume that the families DuBois, Van Meteren, Blanchan and Crispell were rescued in September. It also appears that the children were separated from their parents, so they spent several months being influenced by the natives and their customs.

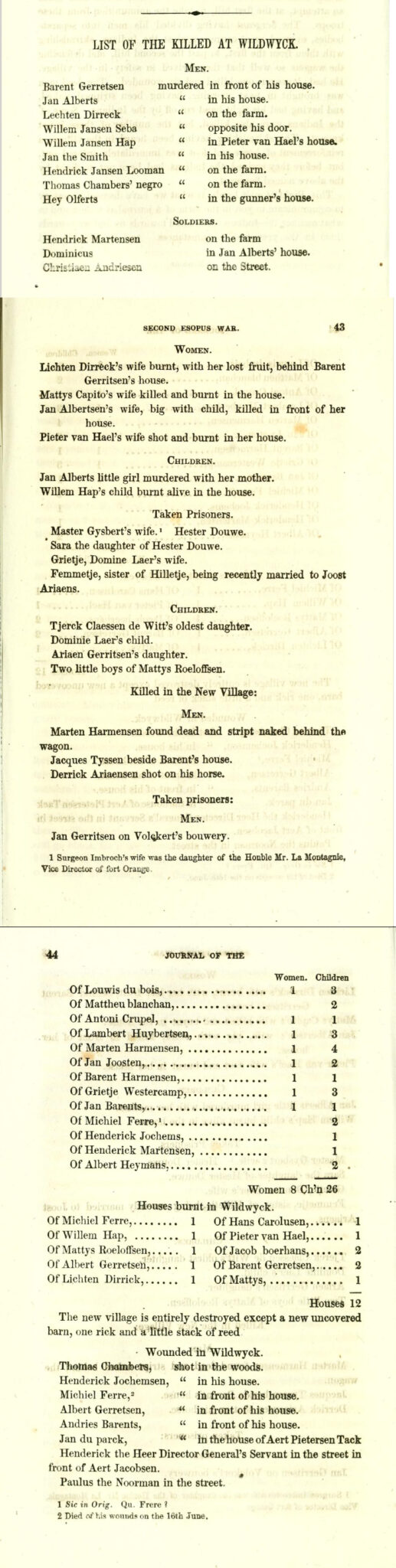

List of the Killed at Wildwyck

The following was clipped from the above mentioned book.

Outcome

The colonists remained suspicious of all Indians with whom they came into contct and expressed misgivings about the intentions of the Wappingers and even the Mohawks, who had halped them defeat the esopus. Colonial prisoners taken captive by the Indians in the Second Esopus War were transported through regions that they had not yet explored , and they described the land to the colonial authorities who set out to survey it. Some of this land was later sold to Frend Huguenot refugess who establish the village of New Paltz.

In September 1664, the Dutch ceded New Netherland to the English. The English colonies redrew the boundaries of Indian territory, paid for land that they planned to settle, and forbade any further settlement on the established Indian lands without full payment and mutual agreement. The new 1665 treaty established safe passage for both settler and Indians for purposes of trading. It further declared “that all past injuryes are buiyed and forgotten on both sides,” promised equal punishment for settlers and Indians found guilty of murder, and paid traditional respects to the sachems and their people. Over the course of the next two decades, Esopus lands were brought up and the Indians moved out peacefully, eventually taking refuge with the Mohawks north of the Shawangunk mountains.

New Netherlands – Smoking the Peace Pipe.5

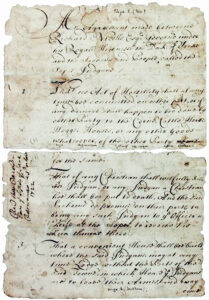

First page of the 1665 treaty between the British colonies and the Esopus tribe forbidding hostility between Christians and Indians, including harming livestock and buildings.6

Citations and Attributes:

- Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org), "Esopus Wars” (Accessed 23 Feb 2023).

- The Documentary History of the State of New York; Arranged under the direction of the Hon. Christopher Morgan, Secretary of State. E. B. O'Callaghan, M.D. Charles Van Benthuysen, Albany, 1851. Vol IV. P.37. https://archive.org/stream/documentaryhisto04ocal#page/42/mode/2up. (Accessed 11 Feb 2018).

- "Louis Du Bois." DuBois Family Association website. http://www.dbfa.org/louis_dubois.htm. http://www.dbfa.org/. (Accessed 05 June 2016).

- Le Fevre, Ralph. "History of New Paltz, New York and Its Old Families (From 1678 to 1820) Fort Orange Press, Albany, N. Y." 1909. Revised Edition 1936. https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=20884. (Accessed 23 Jun 2016).

- New Netherland - Smoking the Peace Pipe. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=494711

- First page of the 1665 treaty between the British colonies and the Esopus tribe forbidding hostility between Christians and Idnians, including harming livestock and buildings. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33456355 (Accessed 23 Feb 2023).