Virginia Before the Revolutionary War

This post covers events in Virginia before the the Revolutionary war. These events impacted our Van Metre families and will shed some light on what these colonists were faced with during this era. Abraham Van Metre acquired land and helped establish one of the first settlements in Ohio County, Virginia in what is now the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

The Ohio Company of Virginia 1747

In 1747, a number of prominent Virginia planters, including Thomas Lee and two brothers of George Washington, Lawrence and Augustine Washington, formed the Ohio Company of Virginia, also known as the Ohio Land Company, a land speculation company organized for the settlement of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, (approximate current day state of Ohio, West Virginia and a bit of Pennsylvania). The Ohio Company was organized to represent the prospecting and trading interest of Virginian investors.2

A charter, which secured rights to 200,000 acres near the forks of the Ohio River, was granted to the company by the British crown in 1749. In return, the Virginians promised to settle 100 families in the area and erect a fort to protect them and the British claim to the area.

Table of Contents

In 1750, Christopher Gist was sent into the Ohio Country to explore it and conduct a survey to prepare for settlement. On the basis of his report, the company selected an area in western Pennsylvania and present-day West Virginia.

The interest of British colonists in these western lands quickly became known to the French who had no interest in sharing the region with their rival. They responded by constructing a string of forts in the contested area. The effort to control the Ohio Country was the most direct cause of the French and Indian War.

Efforts by the Ohio Company were thwarted first by the war with France, then later by the Proclamation of 1763, a British policy intended to restrict the American colonists to areas east of the Appalachians. In 1770 the claims the company were exchanged for two shares in the new Vandalia Company (Grand Ohio Company).

Grand Ohio Company 1749

In 1768, the British government authorized Sir William Johnson to make the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, purchasing land rights from the Iroquois, in accordance with the Proclamation of 1763. Samuel Wharton and William Trent applied for a “despoiled traders” land grant in 1768, and to get approved by the British Crown, they joined with a number of other land speculators to form the Walpole Company, named for Thomas Walpole, a British lawyer involved in the endeavor. The goal was acquiring 2.5 million acres of Ohio Country land. Benjamin Franklin was of the seventy-two shareholders, as well as included George Croghan and Sir William Johnson. the Walpole company, Indiana Company, and members of the Ohio Company reorganized, and on December 22, 1769, formed the Grand Ohio Company. In 1772, the Grand Ohio Company received from the British government a grant of a large tract lying along the southern bank of the Ohio as far west as the mouth of the Scioto River. A colony to be called “Vandalia” was planned. However, the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War interrupted colonization and nothing was accomplished. The company, based in London, ceased operations in 1776.

French and Indian War 1756-1763

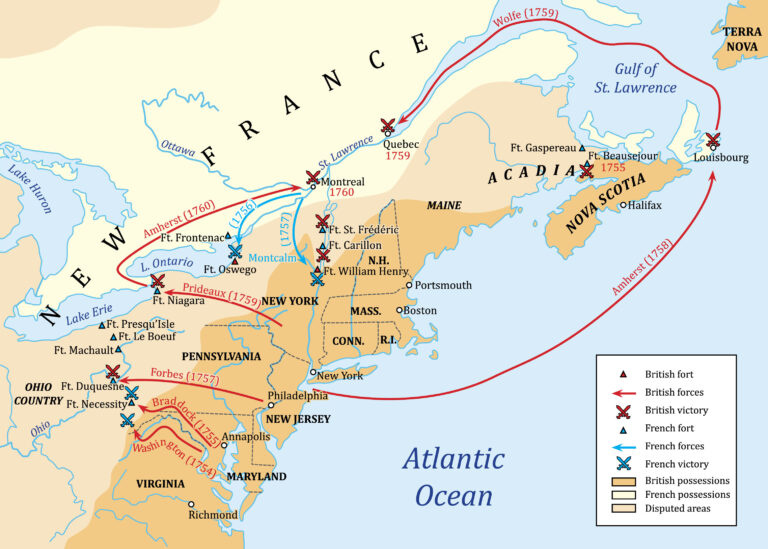

Known by many names including: French and Indian War, The Seven Years’ War, Fourth Intercolonial War, and the Great War for the Empire. The Seven Year’s War refers to events in Europe, from the official declaration of war in 1756 to the signing of the peace treaty in 1763. These dates do not correspond with the fighting on mainland North America, which was largely concluded in six years, from the Battle of Jumonville Glen in 1754 to the capture of Montreal in 1760. French Canadians also use the term “War of Conquest”, since it is the war in which Canada was conquered by the British and became part of the British Empire.

Fighting took place primarily along the frontiers between New France and the British colonies, from Virginia in the south to Newfoundland in the north. It began with a dispute over control of the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers called the Forks of the Ohio, and the site of the French Fort Duquesne within present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

It pitted the colonies of British America against those of New France. Both sides were supported by military units from their parent countries of Great Britain and France, as well as by American Indian allies. At the start of the war, The French North American colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British North American colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on the Indians. The European nations declared war on one another in 1756 following months of localized conflict escalating the war from a regional affair into intercontinental conflict.

At this time, North America east of the Mississippi River was largely claimed by either Great Britain or France. Large areas had no colonial settlements. The French population numbered about 75,000 and was heavily concentrated along the St. Lawrence River valley, with some also in Acadia (present-day New Brunswick and parts of Nova Scotia). Fewer lived in New Orleans, Biloxi, Mississippi, Mobile, Alabama, and small settlements in the Illinois Country, hugging the east side of the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

The British colonists were supported in the war by the Iroquois Six Nations and also by the Cherokees, until differences sparked the Anglo-Cherokee War in 1758. In 1758, the Pennsylvania government successfully negotiated the Treaty of Easton in which a number of tribes in the Ohio Country promised neutrality in exchange for land concessions and other considerations. Most of the other northern tribes sided with the French, their primary trading partner and supplier of arms. The Creeks and Cherokees were subject to diplomatic efforts by both the French and British to gain either their support or neutrality in the conflict.

By this time, Spain claimed only the province of Florida in eastern North America; it controlled Cuba and other territories in the West Indies that became military objectives in the Seven Year’s War. Florida’s European population was a few hundred, concentrated in St. Augustine and Pensacola.

Stamp Act and "No Taxation Without Representation" 1765

The 1765 Stamp act was imposed on American colonists to raise revenue by a duty tax, in the form of various stamps of different denominations, on all newspapers and legal or commercial documents. The documents subject to the Stamp Tax included newspapers, liquor licenses, certificates, diplomas, contracts, legal documents, calendars, almanacs, wills, Bills of Sale and Licenses –the Stamp Act affected everyone in the colonies.

External taxes, such as the Sugar Act, Navigation Acts or Molasses Act has all been accepted as tax affecting trade, a simple import duty. External taxes were not regarded as a burden on colonial economic activity and colonists considered them as compensation for defense, access to European markets or just as cost of doing business with Britain. On the other hand, an internal tax, such as the Stamp Act, was meant to raise revenue. This tax was not accepted by colonists unless it came from colonial assemblies.

During the short period of 1762-1770 the British government had six ministries causing disruption in its colonial policy. Furthermore, it found itself fighting wars in Europe, West Indies and Asia which drastically increased the cost of servicing its national debt. At the top of its agenda was the lightening of the burden on British taxpayers.

Under British view, America was prosperous enough to bear part of the cost of its defense so Britain set to issue a series of legislative acts to tax colonial residents. These acts are an excellent illustration of the socioeconomic forces that destroyed the British colonial empire and led to the American Revolution. The Stamp Act was the first serious American challenge to British power and the subsequent Stamp Act Congress the first attempt to organize the opposition. One of the resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress was that Britain did not have the right to impose an internal tax on the colonies without representation in British parliament. The colonists did not agree with the concept of ‘virtual representation” because they thought they would not protect the interest of British subjects outside Britain. Even physical representation would not guarantee the protection of their rights as they were too far to make informed decisions. They feared that a small tax would be just the beginning of heavier taxation and would eventually destroy their prosperity and assets. However, colonists did agree that Parliament had the power to enact measures to benefit trade but not to legislate and internal American tax.

For the first time, the colonists were united in a common cause against the imposition of taxes by the British. The Stamp Act Congress met in the Federal Hall building in New York City between October 7 and 25, 1765. It was the first colonial action against a British measure and was formed to protest the Stamp Act issued by British parliament on March 1765. The Stamp Act Congress was attended by 27 representatives of nine of the thirteen colonies. Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia were prevented from attending because their loyal governors refused to convene the assemblies to elect delegates. New Hampshire did not attend but approved the resolutions once Congress was over.

The Stamp Act Congress declared the Stamp Act duties as extremely bothersome as the scarcity of specie made its payment impractical. Local profits would suffer from the payment of the duty ultimately affecting transatlantic trade. Congress also supported the boycott of British goods.

The Colonists also wanted to reassert their right to trial by jury as an inherent right to all British subjects in the colonies and limit the jurisdiction of Admiralty Courts. These courts could try a case anywhere within the British Empire; cases were decided by judges instead than by juries. In addition, judges and naval officers were paid based on the fines they levied leading to abuses.

The colonial petition was rejected on the basis of having been submitted by an unconstitutional assembly. The Stamp Act was eventually repealed primarily based on economic concerns express by British merchants. However, parliament in order to reassert its power and constitutional issues over its right to tax its colonies passed the Declaratory Act.

The Declaratory Act was a measure issued by British parliament asserting its authority to make laws binding the colonists “in all cases whatsoever” including the right to tax. This was a reaction of British parliament to the failure of the Stamp Act as they did not want to give up on the principle of imperial taxation asserting its legal right to tax colonies.

Many in the colonies celebrated the repeal of the Stamp Act and did not vigorously protest the declaratory Act. However, the Sons of Liberty including Samuel Adam, James Otis and John Hancock, saw more taxation coming their way.

Boston Tea Party 1773-1774

The famed act of American colonial defiance served as a protest against taxation. Seeking to boost the troubled East India Company, British parliament adjusted import duties with the passage of the Tea Act in 1773. While consignees in Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia rejected tea shipments, merchants in Boston refused to concede to Patriot pressure. On the night of December 16, 1773, Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty boarded three ships in the Boston harbor, disguised as Mohawk Indians, and threw 342 chests of tea overboard. This resulted in the passage of the punitive Coercive Acts in 1774 and pushed the two sides closer to war.

It took nearly three hours for more than 100 colonists to empty the tea into Boston Harbor. The chests held more than 90,000 lbs. (45 tons) of tea, which would cost nearly $1,000,000 dollars today.3

The Coercive Acts 1774

In 1774, upset by the Boston Tea party and other blatant acts of destruction of British property by American colonists, the British Parliament enacts the Coercive Acts, to the outrage of American patriots. The Coercive Acts were a series of four acts established by the British government. The aim of the legislation was to restore order in Massachusetts and punish Bostonians for their Tea party, in which members of the revolutionary-minded Sons of Liberty boarded Three British tea ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 crates of tea–nearly $1 million worth in today’s money–into the water to protest the Tea Act.

Passed in response to the Americans’ disobedience, the Coercive Acts included:

- The Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until damages from the Boston Tea Party were paid.

- The Massachusetts Government Act, which restricted Massachusetts; democratic town meetings and turned the governor’s council into an appointed body.

- The Administration of Justice Act, which made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in Massachusetts.

- The Quartering Act, which required colonists to house and quarter British troops on demand, including in their private homes as a last resort.

- The Quebec Act, which extended freedom of worship to Catholics in Canada, as well as granting Canadians the continuation of their judicial system.

–

More important than the acts themselves was the colonists’ response to the legislation. Parliament hoped that the acts would cut Boston and New England off from the rest of the colonies and prevent unified resistance to British rule. They expected the rest of the colonies to abandon Bostonians to British martial law. Instead, other colonies rushed to the city’s defense, sending supplies and forming their own Provincial Congresses to discuss British misrule and mobilize resistance to the crown.

In September 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and began orchestrating a united resistance to British rule in America.

Gun Control 1774-1775

According to David B. Kopel’s article The American Revolution against British Gun Control4, it was the events – 1774 import ban on firearms and gunpowder; the 1774-1775 confiscations of firearms and gunpowder; and the use of violence to effectuate the confiscations – that changed a situation of political tension into a shooting war. Each of these British abuses provides insights into the scope of the modern Second Amendment.

Battle at Lexington and Concord 1775

On the night of April 18, 1775, hundreds of British troops set off from Boston toward Concord,

Massachusetts, in order to seize weapons and ammunition stockpiled there by American colonists. Early the next morning, the British reached Lexington, where approximately 70 minutemen had gathered on the village green. Someone suddenly fired a shot—it’s uncertain which side—and a melee ensued. When the brief clash ended, eight Americans lay dead and at least an equal amount were injured, while one redcoat was wounded. The British continued on to nearby Concord, where that same day they encountered armed resistance from a group of patriots at the town’s North Bridge. Gunfire was exchanged, leaving two colonists and three redcoats dead. Afterward, the British retreated back to Boston, skirmishing with colonial militiamen along the way and suffering a number of casualties; the Revolutionary War had begun.

Citations and Attributes:

- The Ohio Country, showing present-day U.S. state boundaries. CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1255736

- Bailey, Kenneth P. PH.D., University of California at Los Angeles. "The Ohio Company of Virginia and the Westward Movement 1748-1792. A chapter in the History of the Colonal Frontier." The Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, California, U.S.A. 1939. https://archive.org/stream/ohiocompanyofvir00bail#page/n7. (Accessed 14 Sep 2018).

- History.com website: Boston Tea Party . (Accessed 20 April 2023)

- Kopel, David B. (www.davekopel.org), website. The American Revolution against British Gun Control. 2012.

- The Ohio Country, showing U.S. state boundaries. CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1255736

- Map of the Grand Ohio Company’s proposed colony of Vandalia. This image is in the public domain because it came from the site http://www.demis.nl/home/pages/Gallery/examples.htm and was released by the copyright holder. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this map since it is based on free of copyright images from: www.demis.nl. See also approval email on de.wp and its clarification.

- Map of French and Indian War - By Hoodinski - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30865550